We’re often told that being happy, meditating and mindfulness can benefit our health. We all have that one friend of a friend who says they cured their terminal illness by quitting their job and taking up surfing – but until now there’s been very little scientific evidence to back up these claims.

Now researchers in Canada have found the first evidence to suggest that support groups that encourage meditation and yoga can actually alter the cellular activity of cancer survivors.

Their study, which was published in the journal Cancer last week, is one of the first to suggest that a mind-body connection really does exist.

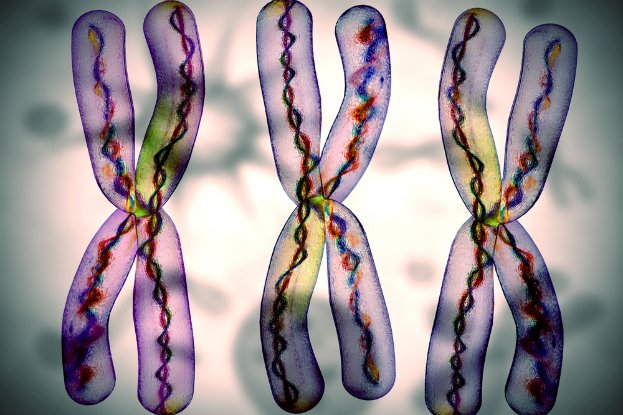

The team found that the telomeres – the protein caps at the end of our chromosomes that determine how quickly a cell ages – stayed the same length in cancer survivors who meditated or took part in support groups over a three-month period.

On the other hand, the telomeres of cancer survivors who didn’t participate in these groups shortened during the three-month study.

Scientists still don’t know for sure whether telomeres are involved in regulating disease, but there is early evidence that suggests shortened telomeres are associated with the likelihood of surviving several diseases, including breast cancer, as well as cellular ageing. And longer telomeres are generally thought to help protect us from disease.

“We already know that psychosocial interventions like mindfulness meditation will help you feel better mentally, but now for the first time we have evidence that they can also influence key aspects of your biology,” said Linda E. Carlson, a psychosocial research and the lead investigator at the Tom Baker Cancer Centre, in a press release. She conducted the study alongside scientists from the University of Calgary.

“It was surprising that we could see any difference in telomere length at all over the three-month period studied,” said Carlson. “Further research is needed to better quantify these potential health benefits, but this is an exciting discovery that provides encouraging news.”

As part of the research, 88 breast cancer survivors who had completed their treatment more than three months ago were monitored. The average age of the participants was 55, and to be eligible to participate in the study they all had to have experienced significant levels of emotional distress.

They were separated into three groups – one was asked to attend eight weekly, 90-minute group sessions that provided instructions on mindfulness meditation and gentle yoga. These participants were asked to practice meditation and yoga at home for 45 minutes daily.

The second group met up for 90 minutes each week for the three months, and were encouraged to talk openly about their concerns and feelings.

The third control group simply attended one six-hour stress management seminar.

Before and after the study, all participants had their blood analysed and their telomere length measured.

Both groups who attended the support groups had maintained their telomere length over the three-month period, while the telomeres of the third group had shortened. The two groups who’d attended the regular meetings also reported lower stress levels and better moods.

Although this is pretty exciting research, it’s still not known whether these benefits will be long-term or what’s causing this biological effect. Further research is now needed to find out whether these results are replicable across a larger number of participants, and what they mean for our health long-term.

But it’s a pretty huge first step towards understanding more about how our mental state affects our health. And it’s part of a growing body of research out there – a separate group of Italian scientists published in PLOS ONE a few weeks ago also showed that mindfulness training can change the structure of our brains.

Of course for many believers in meditation, this discovery probably isn’t that exciting. Research back in the ’80s had suggested that cancer patients who join support groups are more likely to survive. But as we like to say, peer review or it didn’t happen.

We’re (sceptically) excited.

From: Science Alert