For more than 20 years, I’ve considered learning meditation. Quiet spaces! Clean robes! Shaved heads that require no fancy organic hair products! The life of Buddhist monks seems so calm, and we all want a piece of that tranquility. But while I can’t move to a monastery, maybe, just maybe, I could learn to meditate with an app instead.

I’m not alone in this dream. Eighteen million Americans have been drawn to the practice of meditation, which must explain why there are more meditation apps in the App Store than I can count. Meditation’s benefits range from lowering blood pressure to boosting immune systems, and they have been proven by scientists again and again. Mindfulness—the premise of meditation that involves recognizing your thoughts and emotions as they come and go—is a central tenant of one of the most powerful psychological self-treatments, cognitive behavioral therapy.

Forget books. I’d tried those years ago. I wanted to exploit the latest in technology! My iPhone! My VR headset! As a control, I even visited a local Zen Buddhism group to try meditation the old-fashioned way: in person—before I convinced a Buddhist priest to try the app approach, too.

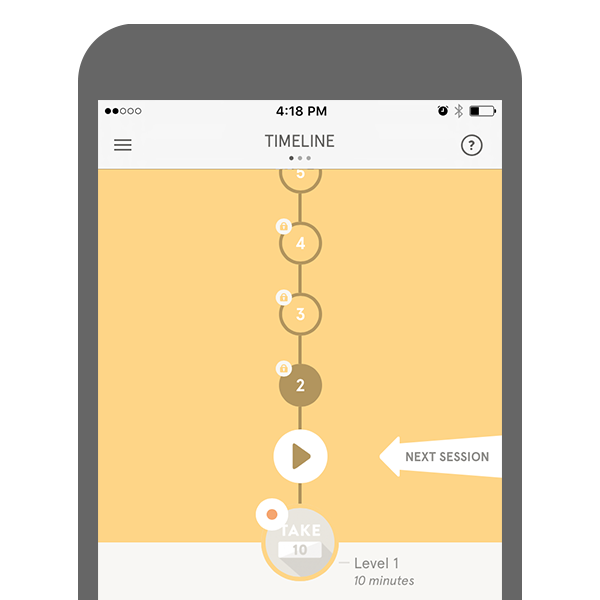

Test 1: The App

He speaks to me with the most enchanting European accent. He tells me to sit down in a chair and get comfortable. He knows it’s my first time.

As his words emanate out of my iPhone’s speaker, I’m suddenly shocked that I recognize the voice. It’s Andy Puddicombe, the CEO of the app Headspace—what’s essentially a subscription podcast for guided meditation. What I hadn’t realized is that Puddicombe is the voice of his own app. A former Buddhist monk-turned-entrepreneur, Puddicombe dresses in well-tailored suits but has kept his cue ball haircut. Having met him before at SXSW, it was obvious how his perfect yin-yang, East-meets-West demeanor allowed him to raise $30 million from a combination of Silicon Valley and Hollywood elite when his product is, essentially, a modern take on self-help cassette tapes.

Rather than a chair, I sit on my couch, but my back is straight and feet are flat on the ground as he’s instructed. Puddicombe runs me through a series of gentle instructions, having me focus on the sounds of my environment, then the most acute sensations of my body. I feel a tight neck down into my shoulder blades.

He tells me to focus on breathing, every bit of it, even down to the way the shirt rubs against my diaphragm. I quickly find myself thinking about my breathing so much the feeling almost makes me nauseous. Am I breathing too much? Too little? Suddenly, breathing felt like the very miracle of my existence. How did I normally breathe every day? I’m working SO HARD on breathing right now, and it’s SO COMPLICATED.

But within a few minutes of his soothing instruction, I’m a meditative puppet in his hands. I find a sort of peace in my own body. I hear the sounds of my environment washing over me, not as distractions or competition but as an extension of my own self. I’m Phil Jackson the Zen master. I’m Naruto in sage mode! “I’m meditating!!” I realize. And as a result, I’m no longer meditating.

It’s a relief when Puddicombe tells me it’s time to allow my mind to wander, to not acknowledge and push away thoughts in my head, but to let them take me wherever they like. Whatever you say, you monkish James Bond.

I see a snail. A cartoon snail, with a lilac shell. I don’t know why I’m seeing this snail, okay? Don’t judge my snail visions. Because suddenly, a free association of snails is popping through my head, from Youtube-style clips to a time a friend ate escargot without knowing what that French word meant.

It’s a powerful, if silly, sensation.

After 10 minutes, when Puddicombe tells me to open my eyes, I’m completely relaxed. I’m not worried about the work I have to complete—it’ll get done—and as I walk back to my computer, I catch a glimpse at an antique doorknob in my home. It’s a doorknob I’ve seen countless times, but its details suddenly pop out to me like a high-contrast photo filter.

I think it’s fair to say, I disliked meditating, but I liked having meditated.

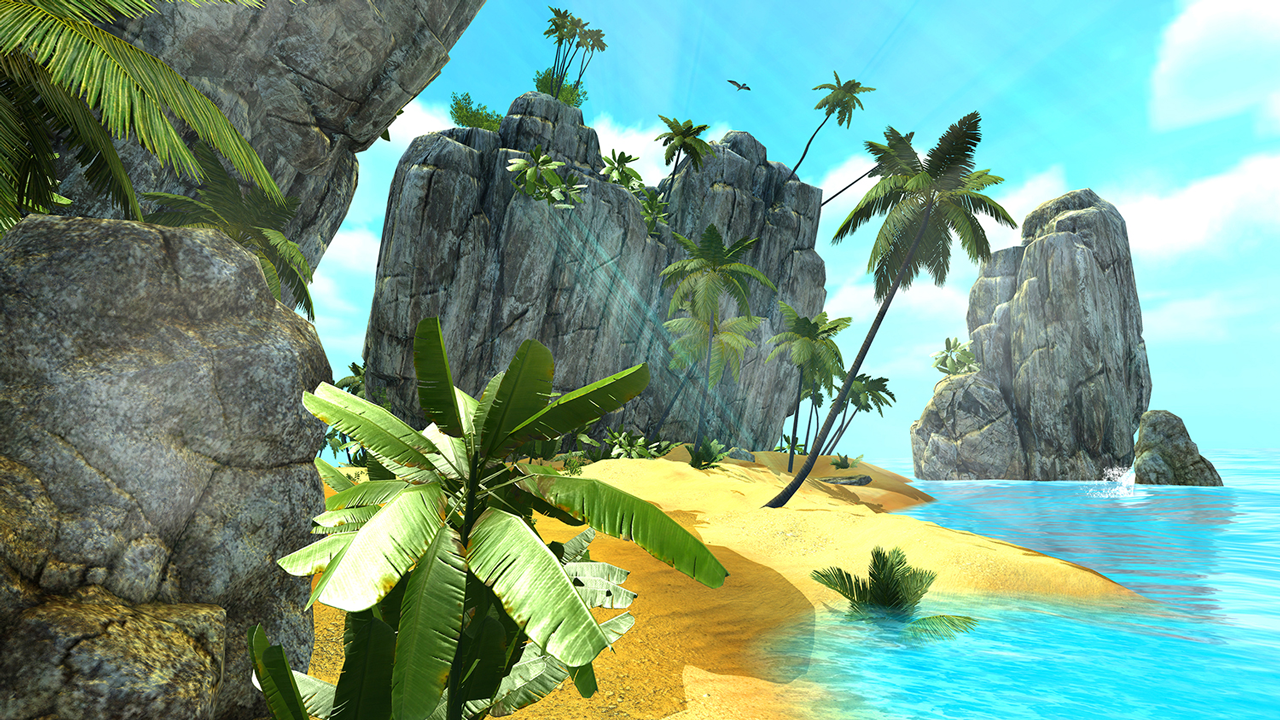

Test 2: The Virtual World

I’m floating above the clouds in a starry sky when a giant button labeled MEDITATE appears with a small gong hit. Guess I came to the right place.

In reality, I’m sitting on the floor of my son’s nursery. But in virtual reality—Guided Meditation VR on the Samsung Gear headset—I’m choosing my ideal meditation environment. A forest in fall? A frigid glacier?

I go with the deserted beach. And as I apparate on white sand, I take a moment to appreciate the pixelated scenery. The waves lap at the shore, birds fly through the sky, light shifts realistically from the clouds—it’s an impressive simulation on a smartphone, even if I feel less like I’m on a real beach than I’m sitting inside some beach chapter of Ready Player One.

Much like Headspace, a narrator comes on and instructs me in the basics of meditation. I realize I’ve heard it all before. It’s almost word-for-word what I learned in Headspace. Of course the fundamentals never change—the breathing, the quest to emptiness—but I begin to realize why you might want to meditate without spoken guidance: No one wants to hear the same spiritual sales pitch again and again.

As I scan through my body, from my head to my toes, I’m reminded that I have a digital scuba mask on my face. I try to ignore it.

Slowly, I let the pixelated environment float into my consciousness. I find my eyes resting on the lapping waves that reflect the clouds—a perfect visualization for a metaphor the narrator offers me, to think of my thoughts as clouds and let them pass. The soundscape in my headphones, too, are effective in transporting me a thousand miles from my Chicago condo. (Little do I know, my toddler has just thrown a bowl of yogurt in the other room.)

Yet I find my peaceful spot when focusing on the truth of the situation, rather than the illusion—that I’m wearing a screen on my face pretending to be in paradise. That I’m just me, here, doing this silly thing. I let the absurdity wash over me like the pixelated waves, and it’s in its own way, peaceful.

Then, a message interrupts my Corona commercial. My phone is overheating and I should discontinue VR apps for optimal performance. I dismiss it, but the world begins to stutter. My 10 minutes is almost up anyway.

Test 3: The Real-Life Buddhists

Thirteen years ago, the young Swede Johan Ostlun “encountered some unprecedented levels of stress and anxiety.” He found Buddhist meditation to be the only relief. So he left Sweden to spend a year in India and Thailand at monasteries and retreat centers. Then came to the U.S., where he studied nine years at the San Francisco Zen Center. He was ordained a Buddhist priest four years ago, when he was given the name Hakusho Hoetsu, or “White Pine, Giving Joy.”

Today, Hakusho and I sit on black cotton mats in the kitchenette of Ancient Dragon Zen Gate (which, full disclosure, I chose primarily because of its convenient hours and the fact that “dragon” was in the name), a local community space for Soto Zen Buddhist meditation in Chicago. Hakusho is giving me a 20-minute crash course before my first group meditation. But so far, my nerves are on end.

After a relaxing, Pokémon-filled walk to the studio, I’d tried to open the center’s front door, only to discover it locked. Even though I barely made a noise when I jiggled the door, I had made my first faux-pas. A woman in ceremonial robes answers the door with a scowl and quickly, quietly, walks away. Hakusho greets me with a smile, and a whisper. The center would make libraries sound like rock concerts.

Hakusho advises me on rites like bowing (to the mats, to the doors, when in doubt, you bow), how to walk around the room (hands held a certain way, and quietly on the balls of my feet), proper meditative posture (your legs should make a triangle to sit upon, cross-legged but with your butt on pillows above your knees so that your legs don’t fall asleep), proper meditative hand posture (known as the dhynana mudra, which to me was designed to feel like the most precarious, ceremonial means of holding a baby bird), what to do with my eyes (leave them a bit open, but look down 45 degrees), and, of course, how to actually meditate (to acknowledge thoughts as they enter your mind, but let them pass, focusing on your natural breath).

As we exit the room, I think to ask how long the meditation goes. “Forty minutes,” he says.

“Will someone be leading it?”

“No, it’s unguided.”

I panic. I’d expected some wise guru would be talking me through my quest toward enlightenment (Zen Buddhists believe that the ultimate spiritual epiphany can strike during meditation), or maybe at least chanting in some way that would make me feel generically spiritual. Instead, I silently claim an open mat that’s up against a plain white wall—a plain white wall that embodies facing inward, sure, but a plain white wall that I’ll be staring at for the near equivalent of one episode of Game of Thrones. Why wasn’t I just watching Game of Thrones? Why did I choose THIS WHITE WALL above all other things I could be doing with anyone I knew or loved, or any hobby I wanted to learn?

I bow. Take a seat, shoving a half dozen pillows under my extremities as Hakusho had taught me to get comfortable. I feel like I’m sitting on a six-year-old girl’s stuffed-animal-covered bed. Someone rings a chime. And, as I can’t see anyone else in the room, I assume that we’re all meditating, and that I’m not the only one meditating while everyone else is making funny faces.

The first few minutes go fine, but increasingly, I realize that this position is pulling on my hips in a way they’ve never been stretched before. They begin to burn, and then burn worse. Plus they remind me that my shoulders are really pretty tight, too. My neck isn’t great either. And my core wobbles around like a tub of yogurt.

I realize that I’m trapped in a sort of personal hell, the aching mindfulness of my own pitiful body. My mind begins a tortuous ouroboros. It starts with breathing, breathing leads to pain, pain leads to ruminating on other topics as a sort of self-preservation technique, and then I remember I shouldn’t be thinking when I should be breathing, and I feel all the pain again.

I glance to the door. I’m so close to the door. It’s just feet away. I consider picking up to leave. And then I remember, it’s sort of my job to be here, and Hakusho came in early to train me. I don’t want to let Hakusho down.

Oddly enough, though, it’s a tip from the Headspace app that keeps me sane: to count my breaths to 10, then start over again.

I feel a giant gold Buddha sitting on my head and forcing my legs into the splits.

Breathe.

How much guitar could I have learned in 40 minutes?

Breathe.

FREE ME FROM THIS PRISON OF FLESH.

Breathe.

When my body hits a threshold of discomfort, I perform a small seated bow as Hakusho has taught me, then I wrap my arms around my knees. Sweet release. It’s so relaxing. It’s, dare I say, meditative! But I feel the gaze of my peers (who are in fact faced away from me). And I begin again.

Breathe.

I come up with all sorts of funny one-liners for the piece.

Breathe.

I forget them (sorry).

Breathe.

If I wanted this pain I should have just done planks.

Breathe.

I bet the only reason monks meditate this way because there weren’t Eames loungers in the sixth century B.C.

Breathe.

Mercifully, someone rings the gong again. At first, I’m afraid to move. What if it’s the sacred “halfway gong?” that nobody told me about. Oh god, what if it’s the sacred “only five minutes have passed gong” that nobody told me about??

But it really is over. We spend the next few minutes chanting while someone hits a drum. The same lady who had scowled at me as I entered noisily had thoughtfully placed a book of incantations at my mat—it was the smallest gesture that made me feel welcome.

Usually, both as a social person and as a reporter filing a story, I would have stuck around to talk to others about their experiences in meditation. But instead, feeling liberated from pain, I race to put on my shoes to escape this meditative Guantanamo. Hakusho catches me before I’m out the door to ask how it went.

“Honestly, it was terrible,” I confess. “My hips aren’t very flexible. I was in pain the whole time.”

“Well, I guess, at least you were in the present,” he says with a consolatory smile.

Test 4: The Priest Tries The App

After my ill-fated visit to the Ancient Dragon Zen Gate, Hakusho and I continue to trade emails. When I ask him if he’s ever tried an app, he explains that while he’d tried some online guided meditation back in the day, it misses out on what draws him to the practice.

“What’s been most supportive for me has been to practice with people, and I’ve tried to arrange my life for that to be possible,” he writes. “The Zen tradition I practice in is often depicted as a transmission ‘warm hand to warm hand.’ There’s something so impersonal about practicing with an app for me; even if it’s been developed by a person, there’s no relationship, total anonymity. If they can help people who aren’t able to practice with others, I’m sure they serve a function, but you’re still going to miss so many of the aspects that come from practicing with others that don’t just have to do strictly with meditation: the sharing, giving and receiving, the practice of taking care of each other and the place, the issues of difficulty with some that will inevitably arise sooner or later as we’re all humans, and the attempts to meet these with a spirit of wisdom and compassion, etc., etc.”

In other words, while meditation itself often isn’t a shared experience, it’s many of the ancillary activities around meditation that Hakusho values—drinking tea together, making meals together, and even cleaning together. But as a good sport—and perhaps to be a more empathetic teacher to students such as myself—he agrees to try the first 10-minute session of Headspace. A few days later, I received this note in my email:

“My impression is that this can be helpful for people who want to meditate and would rather try on their own or don’t have or know of a place around to go to. There’s nothing in the instructions that go against Buddhist meditation instructions as far as I’m aware. So the practice isn’t different, and yet it is, for me at least,” writes Hakusho. “What’s taught is a completely secularized form of meditation, and that’s probably what most people want, to learn to relax a bit. Being guided back into one’s own body is a powerful practice in this regard. But from a Buddhist point of view, meditation is just one part of the practice of waking up, the other two being the practice of ethics and wisdom. I’ve always been drawn to Buddhism for its teachings, including emphasis on living an ethical life, and this was what drew me to meditation.

“As I’m sure you noticed when you visited Ancient Dragon, there’s a ceremonial aspect to our particular form of meditation. I must confess it put me off initially, it looked religious, and I didn’t see myself as someone who was into that kind of stuff. But I still stumbled back into this tradition, and through repetition came to love it.”

A bit over a week into my own experiments, and I actually find the prospect of meditating more overwhelming than when I’d started. Perhaps it’s because I’ve learned just how bad I am at it, and how much practice I’ll need to improve to the point that it’s routinely enjoyable. Perhaps it’s because apps like Headspace are almost anti-ceremonial, so convenient that I can ignore its push notification reminding me to meditate when I have work to file.

That said, I’m impressed at just how good the digital tools are. (I get why Headspace has raised tens of millions of dollars, and I’m still mulling a subscription.) But the even more surprising thing was what I learned from a Google Maps search. If I’m compelled, there are centers of meditation all around me, and people like Hakusho who will go out of their way to share their knowledge. No doubt, an app makes for a light commitment. But if you want to significantly change your life, there’s no replacement for warm hand to warm hand.

From: Fast Company